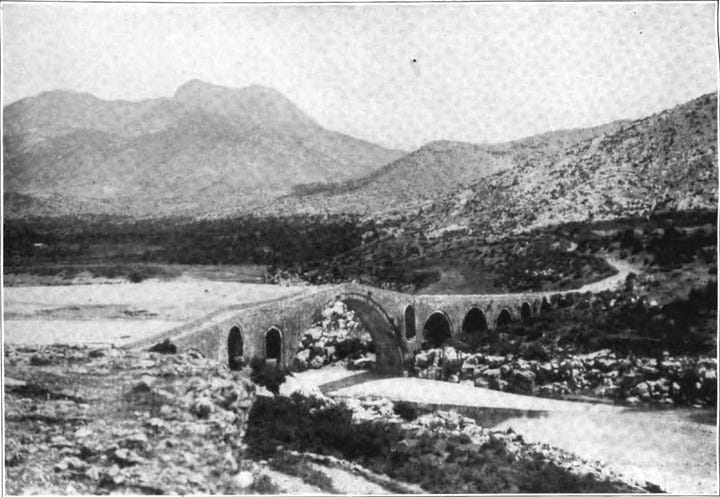

Gilberting the Mesi Bridge in Shkodër

In which through a mix of uncanny confidence and luck I encounter my first Rose Wilder Lane Albanian landmark on the Scutari Plain

I didn’t know the purpose of my trip Shkodër until I saw it. And in the way of people for whom things work out, my first instinct was to attribute my success to destiny and/or cleverness.

But what I’d really experienced, was Albanian-ness.

When I told Albanians of my plans to spend an extra day in Shkodër, I noticed the droopy face, meaning, “Ehhhhhh.” Given that Albanians are inexhaustibly enthusiastic about their country, I sensed this shot across the bow.

Now that I’m here, I see that the city is more of a stop en route to the northern Albanian Alps, a sort of Base Camp One. A perfectly fine city, but not a reason to fly across the world.

I do enjoy a delicious meal of meatballs, fresh feta, tomatoes, cucumber, bread, grilled vegetables, and green salad—after which an unexpected (I thought the previously mentioned was dinner) entrée arrives, a creamy, bechamel-sauced vegetable lasagna made with fresh pasta, followed by Tri-Leche cake, which I now know is not only a Mexican dessert but Balkan.

It would be rude NOT to eat it all, right?

Skoderer is the “bicycle city,” although a Dutch couple I met had something to say about that (“Um, have you been to Amsterdam?). The city is flat, and you see more cyclists than in Tirana. Free use of a bicycle came with my hotel room and what else do I have to do?

“Please wear a helmet,” my boyfriend says.

“I don’t think they have those here,” I say.

Secretly I’m glad because I hate helmets and love how Albania is like the 90s—no helmets, seatbelts, or dog leashes, and people still smoke (outdoors). I put my bony Irish ass on the old cruiser with a basket and pedal away.

I’m doing it!

I didn’t learn to ride a bike until I was ten. This might be due to constant ear infections or my general scairdy-catness. I don’t know, but I still feel triumph every time I take off.

Traffic regulations are more like suggestions here. People double park with flashing lights along the road. Shkodër has bike lines—but they abruptly end at random moments.

Then I hit my first roundabout. I wonder if this is where my corpse will be airlifted out of Albania, all of the Apple News readership tsking me for the ten seconds I’m a news headline. (Was she wearing a helmet? No? At least she wasn’t young). Cars go counterclockwise around the roundabout, but cyclists go whatever-wise. I copy locals, who pedal slowly but surely on their old cruisers.

Although traffic is chaotic, drivers are aware of cyclists. They aren’t angry at bicycles for existing or trying to run them down. Everyone takes their turn. Cycling isn’t an ethos or an identity, just a way of getting around.

The town center feels too touristy to me—bad music, hustlers, and trinkets—so I head the other direction, where I find a park. AH! How quaint is this? I cross a bridge. All I’m missing is a baguette in the basket even though Albanians don’t bake them.

Then I make the wrong turn.

I do that thing where you travel one block too far into the wrong neighborhood. Like poor areas anywhere, that means stray animals and men who make sucky face noises. I did not stop to take a picture.

Sidebar: In Albania, I have thus far experienced, overall, way less random yelling than in my college town of Athens, Ohio.

Still, these streets have that bad vibe. I turn back.

After that, I’m feeling less Gilberty blond and more Bronze Chestnut #45 and concede defeat on the day. In my twin bed I read High Albania by Edith Durham—British anthropologist and writer who preceded Rose Wilder Lane by ten years—until I couldn’t take any more intricate descriptions of feudal Albanian blood oath transactions.

After breakfast, I have five hours before I leave. I’ve been connected with a driver who waits until his car is full, which he estimates to be about 1 or 2 p.m. Have I mentioned there is no public transportation in Albania? Buses, yes, but they are private and involve taxi rides to the depot stations.

I confirm for the third time that checkout is at 11 a.m. I’m pretty sure the clerk, a young woman, is wondering if I’m nuts.

“Still 11,” she says and hands me the key to the bicycle lock.

This time I turn right. North, okay? I turn North. This direction is much better.

Then I see what I really came to see although I didn’t know it until this instant: a familiar-looking bridge. Instantly I know it’s the same bridge I’ve seen many times in The Peaks of Shala (Rose’s travelogue of her crossing the Albanian Alps). This Ottoman bridge, of all the Ottoman bridges, is special for me because it’s the same bridge Rose Wilder Lane crossed 100 years ago.

That I had to stumble upon the Mesi Bridge rather than plan to see the bridge is a little embarrassing. To be fair, in The Peaks of Shala, the caption for the photo reads “The Keri Bridge.” Also, Shokdër was then the “citadel of Scutari.” But I found the bridge anyway.

Within a minute of returning to the hotel, my connection calls to say that the driver is ready to leave at the exact moment I want to leave.

I could say I’m Gilberting again, but no, I’m Albanianing.

A westerner such as myself gets nervous as she wobbles her bicycle into the roundabout, but so long as she trusts the people around her, everything works out here. I’m coming to understand why Rose loved it here.

As always, I'm glad you're alive. As a fellow essayist, I am a little curious about your experience of finding the bridge, of entering into the same place as your book's subject as you retrace her presence there. Or is that material you're saving for your book? [smiling immersion essayist's face emoji]