Sublime Ruination

In which I climb the Pyramid of Tirana

We could blame the Time-Life book, Mysteries of the Unknown: Mystic Places. Or we could point a finger at The $10,000 Pyramid game show, or the endless hype surrounding the King Tut exhibit in the 70s. For what is probably a mix of all the reasons above, the minute I saw “Pyramid of Tirana” on the city map, I was terribly excited about seeing it.

That the pyramid was not ancient in the least and kinda cheesy made me even more excited.

I donned my floppy hat and made the short walk to the city center of Tirana. Behold:

The Pyramid of Tirana was constructed in 1988 as a memorial museum to communist dictator Enver Hoxha, who terrorized and held his country hostage for forty years. To everyone’s relief, he died in 1985. The structure was co-designed by his daughter, an architect.

Given the holy hell Hoxha caused, I can’t blame the country for wanting to tear the pyramid down, but I’m glad they didn’t. The delightfully terrible edifice of egoism remains. Australian architect Peter Wilson describes the Pyramid in Some Reasons for Traveling to Albania (2019) as a “sublime ruination” and “a dystopic ruin used for film sets and unsanctioned urban alpinists,” such as skateboarders who run down the sides.

The pyramid also attracts writer tourists who have traveled to Albania to investigate the story of Rose Wilder Lane. Lane, of course, moved back to Missouri in 1928, years before World War II, much less communist rule, but one reason cited by historians for her leaving is a foreboding sense of European political upheaval.

And upheaval it was to be for sure, although 1928 strikes me as premature for someone as adventurous (some say impetuous) as Rose. I’m reading the idyllic childhood memoirs of British naturalist Gerald Durrell’s time in Corfu (a Greek island visible from Albania’s southern Adriatic coast), who lived there from 1935 to 1939. His life is all delightfully quirky dinner parties, sea turtles and views of the Albanian mountains.

The plan is to pour over Rose’s letters and diaries at the Herbert Hoover Library and read the tea leaves for myself, so for now, back to the Pyramid.

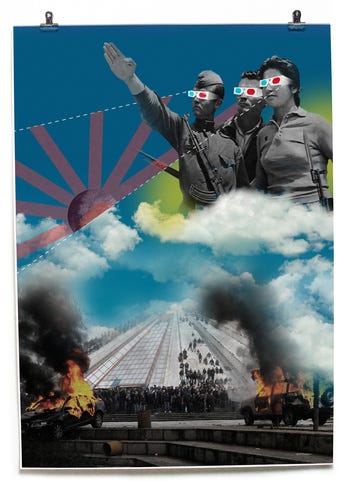

This print sits on the counter of my Airbnb:

The print and copy is by Olio Miho, a design architect from Chicago. She completed a Master’s project at the University of Cincinnati called Concrete Cathedrals. Speaking as someone who lives in Ohio, I say, again, that ALL ROADS lead to and from Ohio.

Fun fact: I have an Albanian colleague at Ohio University who studies how the Albanian economy nearly collapsed in the 1990s due to pyramid schemes. The story goes that the Albanian desire to embrace capitalism drove the people straight into Amway’s toxic, unloving arms.

I wonder—were Albanians more susceptible because this enormous pyramid sits in the middle of their capital city? That this pyramid made them think: Pyramids are cool. (I say this in my head the way the Eleventh Doctor in Doctor Who says, “Fezzes are cool.”)

The pyramid IS cool, but the day is hot. I look up the stairs and all the tourists climbing up. Do I really have to follow them? This is how travel goes. The imagined versus the real. I don’t even see any skateboarders.

At this point, I’ve climbed many tourist stairs. Sometimes, the stairs are just stairs to wear the tourists out. Other times, the climb is worth it. For instance, the City of Lights from the Eiffel Tower at night is unbelievable. Especially if you take the elevator instead.

I didn’t fly all this way to not climb the stairs.

At the top of the pyramid, I see the mountains, how Tirana lies in a valley, and how the city is laid out. Tirana has narrow streets lined by trees, and while the green is nice, I can’t orient. Now I have an idea of where I am.

The streets would have been narrow, but I wonder if Rose had views of the mountains from her Tirana house the way I did when I lived in the smaller mountain cities of Missoula, Montana, or Cedar City, Utah.

Along with mountains and buildings, I see cranes everywhere. Construction is the national obsession as Albania rushes to catch up, but the communist era has left its architectural imprint, including this commemoration/sublime ruination, which has evolved into a monument to the people who survived.